We decided to walk around the old Arab city of Jaffa, which Rachel described as “a lanced boil on Tel Aviv’s thigh.” It was a hot July day, and we were happy to take a walk after our leisurely lunch on Sheinkin St. We asked to be seated as far away from the door as possible, and preferably behind one of the concrete pillars.

Though my companion told me that I had no reason to worry nowadays, I was incredibly nervous about the possibility of exploding people. I had the gazpacho and yam fritters, while my friend had the basmati rice with grilled vegetables. The lunch was perfect, even though the owners’ present of a free “iced tea,” made for some reason with cinnamon and lime, nearly made us gag. We asked the guard standing at the door of the restaurant where the beach was, and he pointed the way.

It didn’t take us long to reach the place, though with each step, the scene became more and more sordid, and also more familiar. It reminded me of Santa Monica, but Noah insisted it was more like Long Beach, with its penny arcades, $1 stores, and junkies lurking in the corners. The beach itself, however, dispelled these comparisons, with its crowds of sunbathers and its rustic-chic beach shack cafes. Above us, a long line of helicopters was heading south, “Toward Gaza,” Rachel explained when she saw me looking. As we started walking south along the boardwalk, we noticed the signs, in Hebrew, English and Russian, announcing the danger of jellyfish. “This is a problem every year,” Noah mentioned. I nodded. We walked and talked, we hadn’t seen each other in a year and there was so much to catch up on.

.jpg)

Noah’s organization, the Zurich Proposal, had folded since I last saw him. Some lefty Israelis had started it in the wake of the collapse of the Oslo Accords, hoping to restart negotiations between Palestinians and Israelis through private initiative. Noah shocked me when he said, with his typically American commonsensical tone, “A pox on both their houses. The Israelis for their occupations, the Palestinians for their idiotic Qassams. They really do deserve each other.” That was how he let me know that his experiment at aliya was coming to an end soon. As we walked, I looked to the east and took pictures of the bright postmodern buildings that had gone up since my last visit. The skyline was indelible, though it would take some time before it became landmark familiar like those of more permanent cities. We passed a set of clubs on the beach, whose signs appeared in Hebrew and Russian. In front of them was a small monument to the victims of a bombing that took place in them only few years ago. I recalled the event, but I couldn’t remember any of the details. I think the bomber had come from Tulkarm, but I’m not sure.

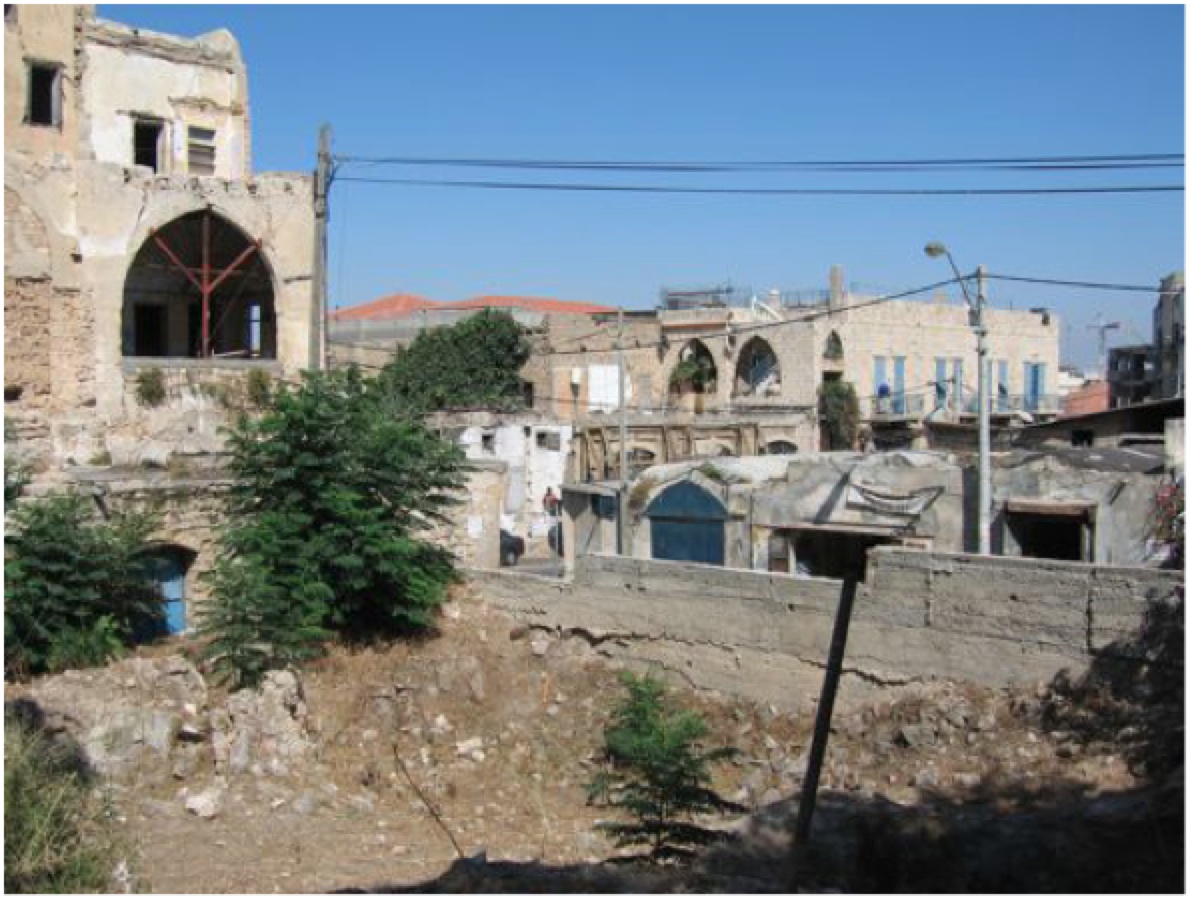

The path turned back to the water right before we arrived at the crumbling set of buildings called “Jaffa.” We followed a small bridge over a storm runoff ditch. The stench was sharp in our noses. When we crossed, we realized it was due to the municipal sewer construction going on behind a row of summer restaurants perched on the cliff over the beach. We walked around it and read the historical sign on the side of the building, “Police station from Ottoman period.” I remarked that I’d read somewhere that, after WWI, it became a British police station, and then following 1948, an Israeli police station. This information was not on the sign, neither in the Hebrew nor in the English. Unfortunately, someone had covered over the Arabic translation with black spray paint, so we couldn’t read that to compare.

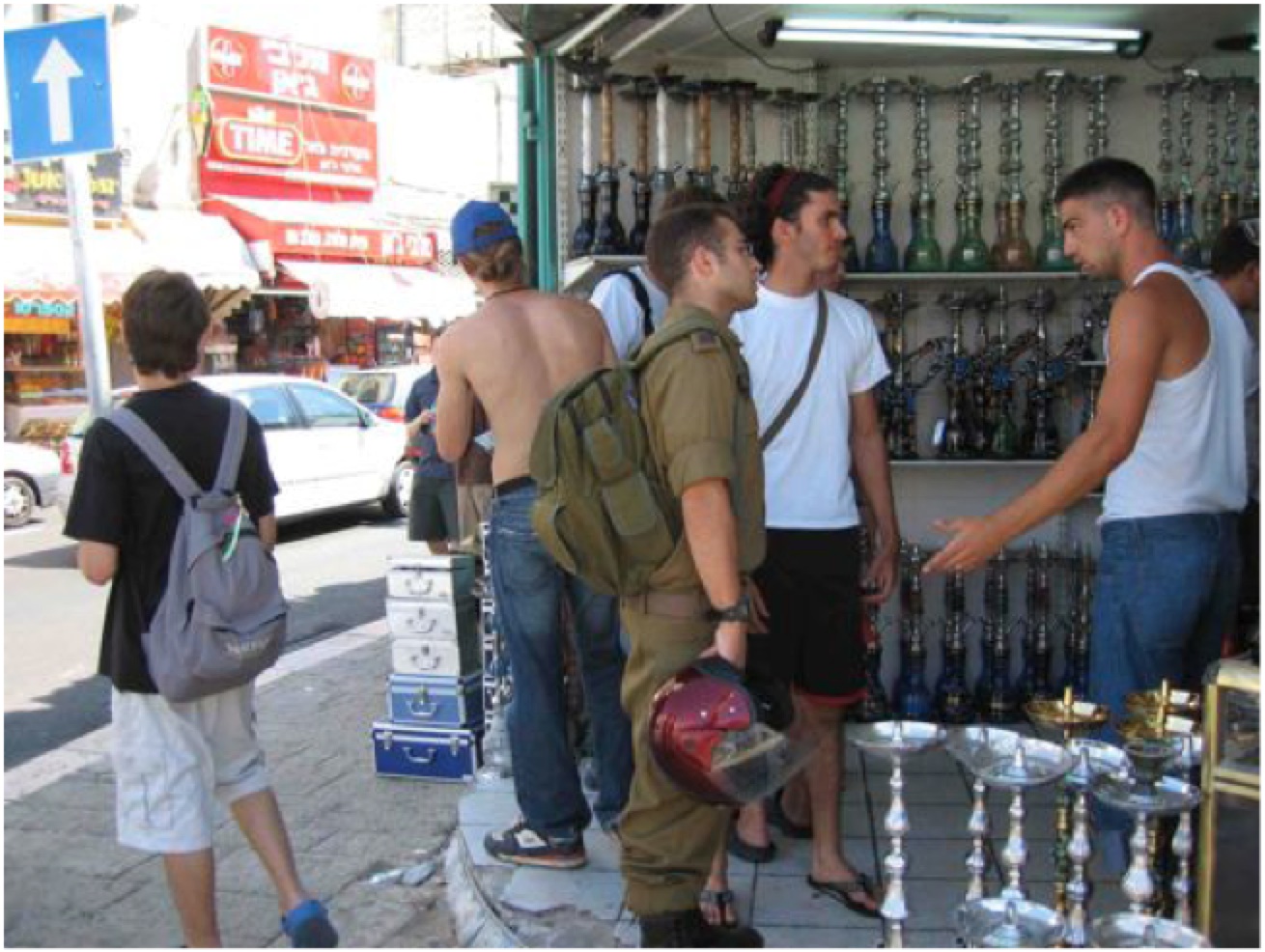

We turned onto the main square, with the clock tower. American college students and Israeli teens swarmed around a shop selling arguileh pipes. The customers bargained ferociously with the shopkeepers who responded with reasonable, partial reductions in price. It all seemed overly scripted. Noah suspected they were on their Birthright Tour. Later, when we saw them getting on their bus, we saw his guess had been correct. We walked over to Abu al-‘Afiyya, the famous Arab pastry maker in Jaffa, and I bought a sweet. I told them that friends in Jerusalem had insisted that I visit their shop and they smiled. The truth be told, however, the baklava was not very good compared to what you can find in any town on the West Bank. We wanted to visit the “souq,” now called a “flea market.” The vendors all seemed to be Russians and Oriental Jews. Most of what they sold, besides the old clothes, was third-rate porno, the kind with chiseled Aryan studs and moaning anorexics with overstuffed breasts. Noah and I laughed, and we wandered among the antique and junk stores.

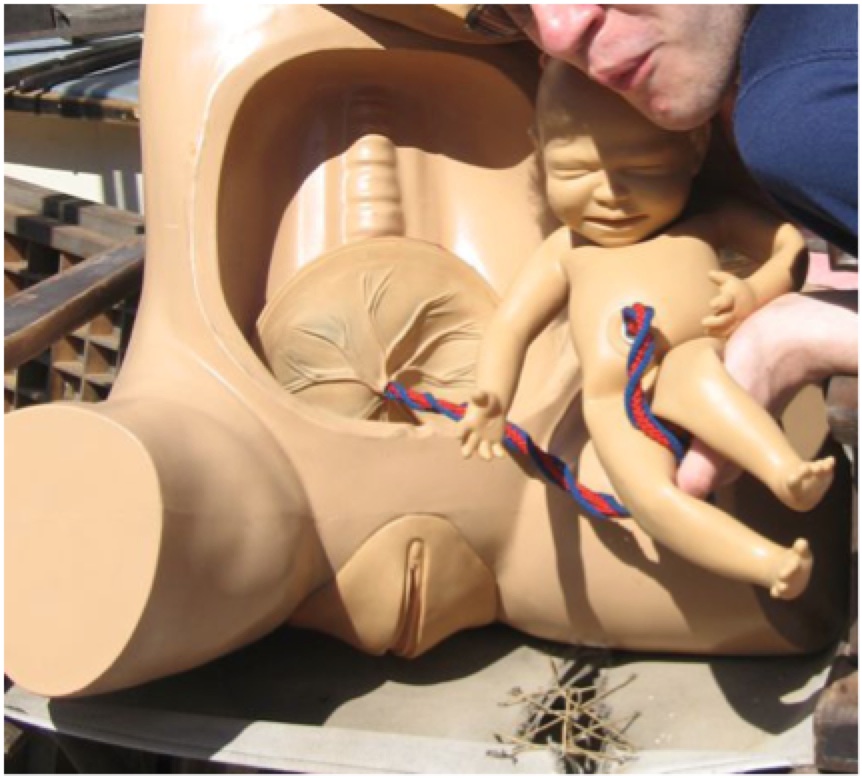

We saw a rubber torso, with rubber breasts and rubber vaginal orifice, with a removable rubber stomach, beneath which was a rubber fetus and placenta. I took a picture, and later when I looked at it, I couldn’t get the word “stillborn” out of my mind.

We walked over to the more upscale part of old Jaffa. It was upscale for one reason only: no one lived there. It was filled with restaurants serving vaguely Mediterranean food, galleries selling “contemporary art,” slick bars and niche clubs, with suggestively oriental names like “Caliph,” “Hammam,” and “Mameluke.” We also found a large S&M club located in the basement of what used to be Jaffa’s city hall. It didn’t seem real.

We walked down to the old port, where a couple busloads of Palestinian kids were taking a tour. They played and ran and pointed at boats, they pointed at the breakwater, they pointed up the hill back at the old city hall. They screamed with delight at everything they saw, and skipped and ran from one sight to the next. We asked one of their teachers who told us they’d come on a day trip from Jerusalem and that most of the kids had never seen the sea before. We decided to walk back to Tel Aviv on the beach itself. I wanted to feel the water on my feet. On the Palestinian beach, families sat close together while a man with a horse sold rides to kids. More than once, horse and rider bolted by us along that stretch, followed by a barking dog. We noticed the horse shit on the sand, bits washing away with each wave. We also noticed that just past where sand met sea was a line of milky white bodies.

.jpg)

I looked north, and saw this line of dead jellyfish stretching out as far as I could see. It followed the contours of the beach, like a trail of placentas leading from one city to the next.

I looked at the shallows and saw that they were relatively free of the creatures. People were playing in the water and bodysurfing. Though Noah wouldn’t, I decided to take my chances and wade as we walked. The water was clear and warm.

We passed mothers and their naked children building sandcastles. We passed teenagers playing soccer in their bathing suits. We passed a bikini-clad woman striking yoga position on a sand bar out in the waves: warrior one, triangle, warrior two, down-dog. We passed a couple of cafes where patrons smoked arguileh and drank espressos. We passed the Russian discothèques. I guess we were so busy talking about Noah’s plans to return to the States, and I was so busy looking around me at all the bronze bodies, that I had long stopped paying attention to the water I was walking in.

It’s a miracle I wasn’t stung more seriously, considering how many there were of them around me. My foot and ankle swelled up like a balloon. A quick-thinking waiter rushed out from a cafe and poured cans of cold club soda over my foot as I sat cursing on the sand.